Better Marketing through Subtraction

We tend to think of marketing as a way to add clients and profits.

But it can also be a matter of subtraction.

Here’s a simple exercise to illustrate that point. Review your roster of open cases. Make a list of all those that:

- Are generating income;

- You enjoy working on;

- You would welcome repeat business from.

Now imagine what would happen if you could dump the remainder – those that aren’t profitable or pleasurable – and be done with them forever.

Your life would immediately become simpler, right? Saner. More successful - without spending a penny on marketing.

Such is the power of subtraction.

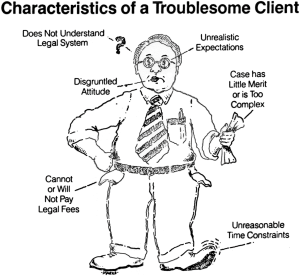

Choosing Wisely Up Front

Of course you can’t just snap your fingers and make your horrible clients disappear. But with better client screening you can avoid inviting them into your life in the first place.

Here are seven questions to ask before saying yes to a prospect.

- Do you have the time to take on the case? If not, say no – regardless of the merits of the matter. You can always refer the client elsewhere.

- Do you have the resources to take on the case? If not, say no. Otherwise you may find yourself making decisions based on economics rather than the client’s best interests. That’s a good way to get sued for malpractice.

- Does the prospect have the money to pay you? “Taking on a client who cannot afford your services serves no one,” says Mark Bassingthwaighte, risk manager at ALPS. “It’s a fee dispute in the making, a collections problem regardless, and often ends up with your having to write off a significant portion of the bill. If this is a contingency fee matter, you might also ask yourself if this matter makes economic sense. For example, if it is likely that the client will come out with less money that what will be owed to you, I’d seriously question moving forward for similar reasons.”

- Does the prospect assure you “It’s not about the money, it’s about the principle of the thing?” If so, back away slowly. Then begin running.

- Are you the latest in a string of attorneys for this client? If so, follow the advice in the above paragraph.

- Have other attorneys met with the prospect but passed on the case? This indicates something is not quite right here.

- Is the prospective client a family member or friend? If so, proceed at your own risk. Remember: no good deed goes unpunished. And heaven forbid you start treating Cousin Ned like a real client – i.e., by opening a file and sending a bill.

Ending a Bad Relationship

Sometimes, though, even the most rigorous client screening won’t prevent a dud or two from slipping through.

That’s when subtraction – by way of firing the client or otherwise ending the relationship – could come in handy.

- Some breakups are mandatory. Under Rule 1.16, a lawyer shall withdraw from representation if: 1) the representation will result in a violation of law or the Rules of Professional Conduct; (2) the lawyer’s physical or mental condition materially impairs the lawyer’s ability to represent the client; or (3) the lawyer is discharged.

- You don’t have to work for jerks – or for free. Withdrawal is allowed when a client engages in conduct that is “repugnant or imprudent” or does things you fundamentally disagree with. Such as not paying your bills.

- Withdrawal is optional if you can do it without hurting the client. The test under Rule 1.16 is whether withdrawal can be accomplished without “material adverse effect on the client’s interests.” Obviously, the earlier you drop a bad case, the less likely your withdrawal will cause material harm. A key factor: has the client paid you a lot of money but gotten little or nothing in return? If so, your withdrawal might well invite a Bar complaint or malpractice claim.

- The less said, the better. “[W]hen deciding to end the relationship, professionals should make sure not to disclose any sensitive or confidential information, including revealing that the client is not paying bills or engaging in improper activity,” advises Professional Liability Matters. “Of course professionals should take steps to make the withdraw as smooth as possible by helping to retain a replacement if appropriate, securing and transferring all files, and making itself available as a resource for the new professional if a need arises.”

- Document your withdrawal. Send the client a disengagement letter. Contact Lawyers Mutual for sample letters and disengagement advice. Return all property and unearned fees.

Have you fired a client recently? How did it go? Do you have any tips for others in the same predicament?

Sources:

- Seth A. Laver, Professional Liability Matters http://professionalliabilitymatters.com/2014/08/06/dropping-the-problem-client/

- Mark Bassingthwaighte, ALPS Property & Casualty Insurance Company http://www.alps411.com/blog/managing-your-practice---musings-of-a-risk-manager/getting-it-right-with-client-selection?sthash.G1yxYSGI.mjjo

- NC State Bar http://www.ncbar.com/rules/rules.asp

- Lawyers Mutual Liability Insurance Company of NC http://www.lawyersmutualnc.com/

Jay Reeves a/k/a The Risk Man has practiced law in North Carolina and South Carolina. Formerly he was Legal Editor at Lawyers Weekly and Risk Manager at Lawyers Mutual. Contact him at 919-619-2441 or jay.reeves@ymail.com.